LGB’s Market Commentary for Q2 2024

The second quarter was generally benevolent for equities. As the chart below shows, the US continued to be the outperformer, but this was rather more broadly based than in the recent past. The UK markets rose more or less uniformly- large medium and small together. The exception was Europe, and that was largely related to the twin electoral shocks of the EU elections followed by President Macron’s decision to force a trial of strength against the right wing RN party. It would be fair to say that Macron’s decision – unforced – was surprising and hard to account for, even from the UK where Rishi Sunak’s surprising decision on the timing of the General Election was against the background of a ticking clock.

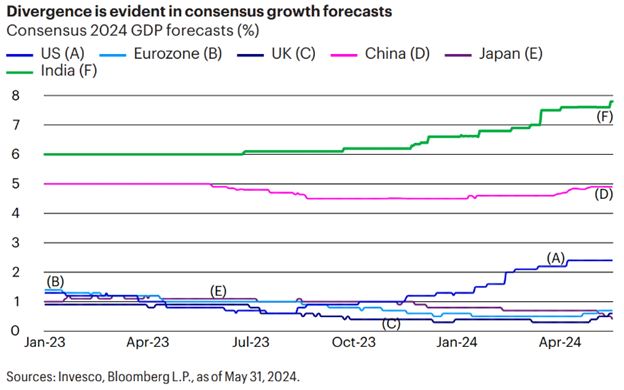

With no major new macro developments (it is still a picture of the US markedly outperforming the UK, EU and Japan, and much stronger growth being seen in India and China), it seems worth spending a little time on politics in this commentary. The below graph gives a useful general picture and shows the trend of increasing optimism for the USA (and India and China), and a decline for Europe.

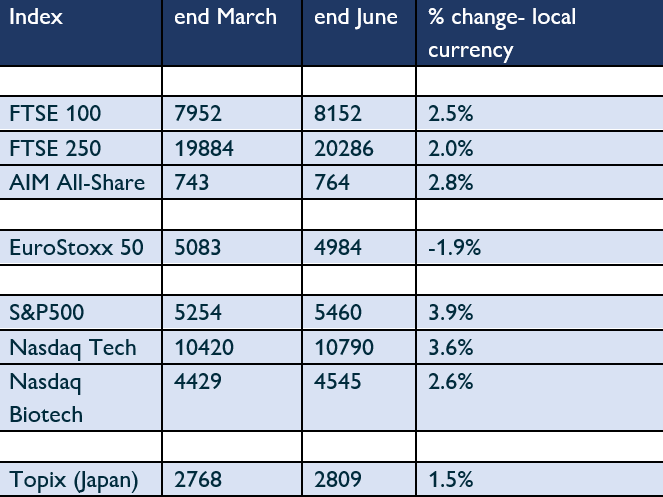

Here are the moves in the equity markets:

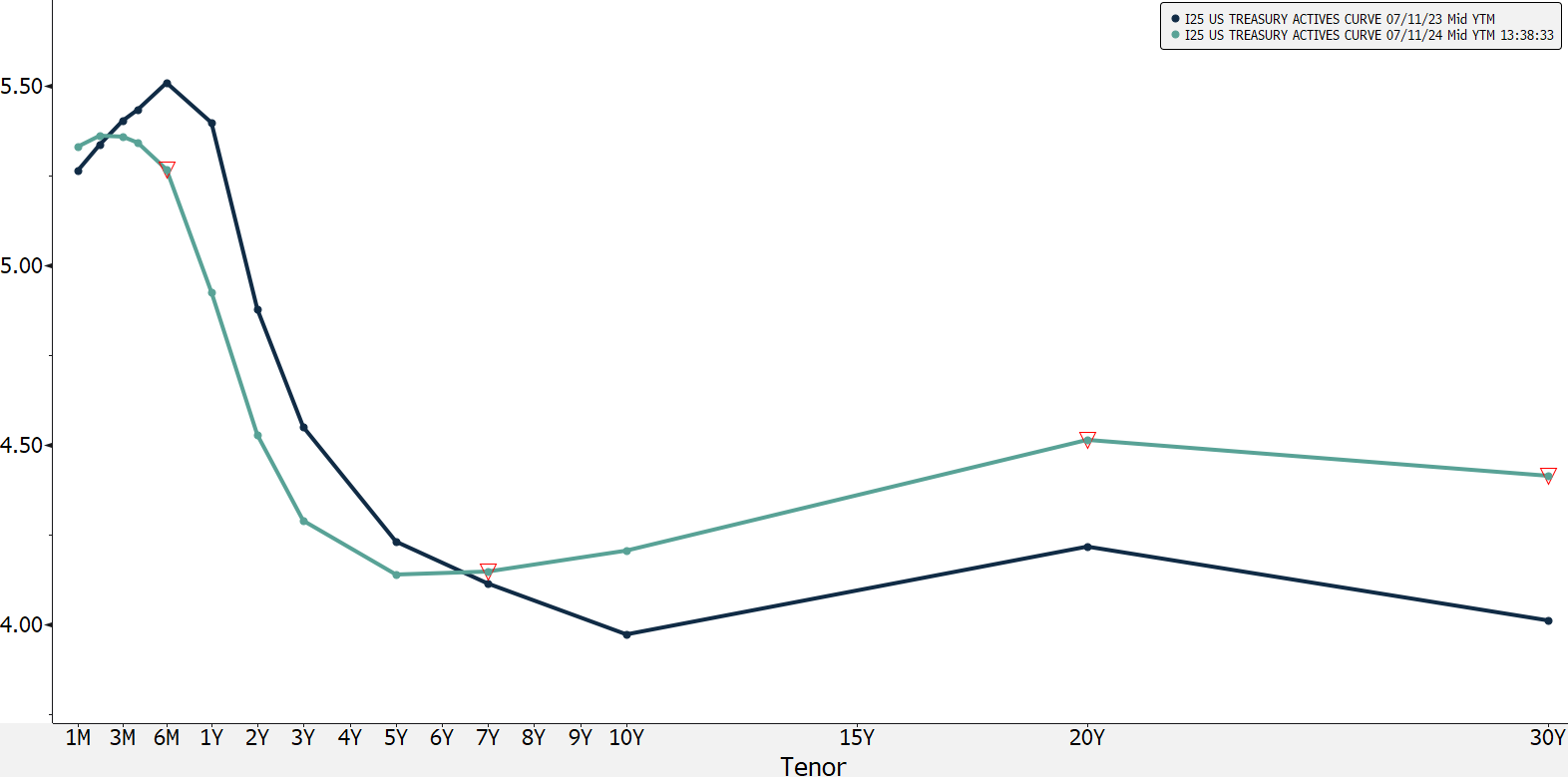

It has not been so agreeable for bonds: US 10-year yields rose a little in the quarter (4.205% to 4.402%), and continued US economic strength does now seem to be feeding through into the realisation that US rates can stay stronger for longer…

![]() Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

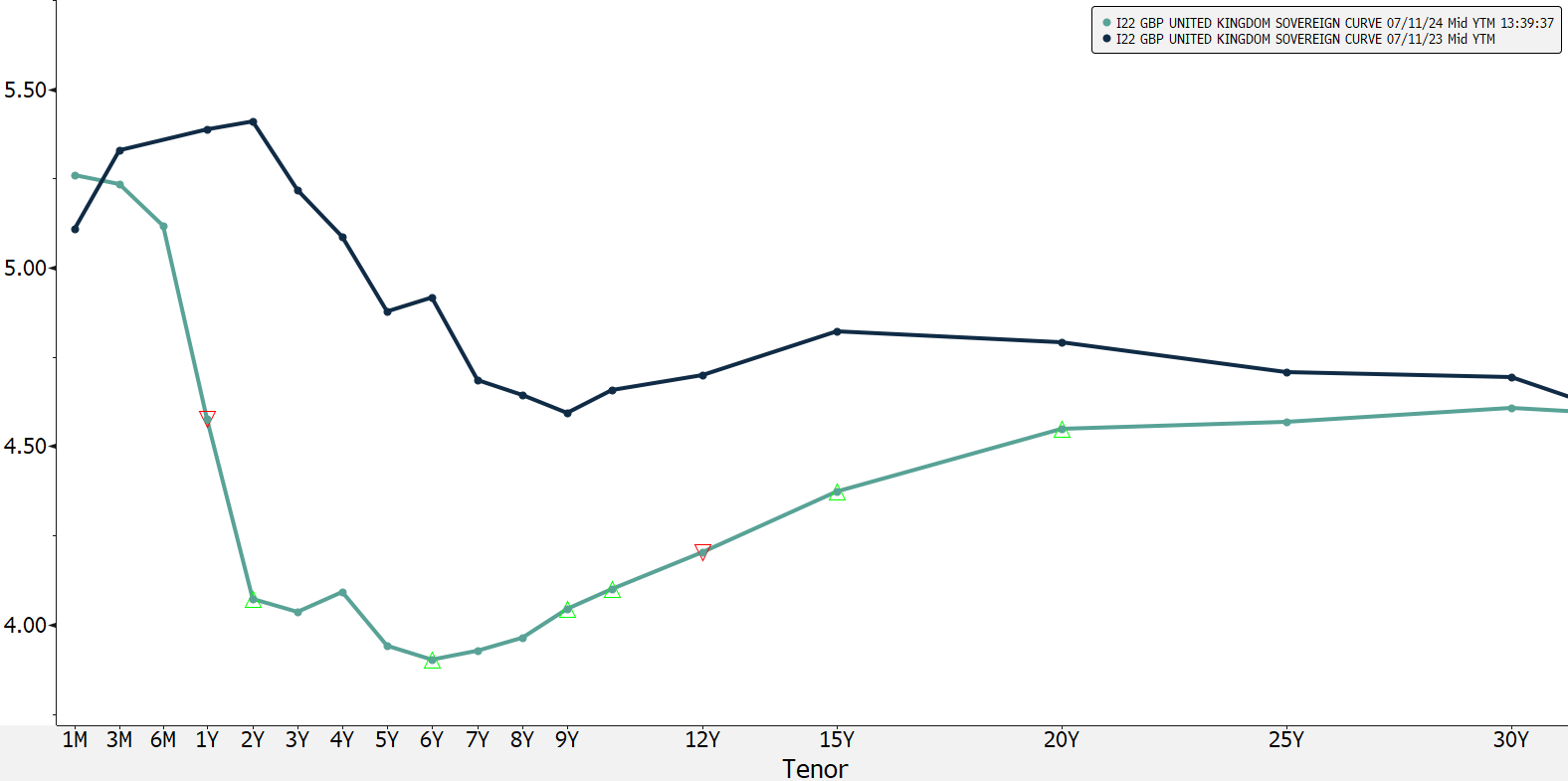

And whilst the Gilts market is a lot more settled than a year ago, 10 year yields were up by a similar amount to the USA over the quarter (3.94% to 4.174%) and short rates have so far barely dropped despite a consensus that the Bank will bring them down later in the year. Lower energy prices might pull UK inflation down in H2- but current high service price inflation (running at around 7%) will definitely work in the opposite direction.

![]() Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

The consensus remains that inflation is slowing, that central banks will look at trends rather than at current inflation levels, and that a meaningful fall in rates is just around the next corner (except in Japan). Psychologically this feels like anchoring of expectations. We’ve got used to low single digit interest rates, they made life easy, so they must be about to come back. Yet the rates of the last few years were by historical standards extremely low and it may be that there is still too much wishful thinking baked into assumptions.

Fidelity provided this useful chart of rates since 1990, which they use to argue that spreads for high yield sterling bonds are too low, but equally it can be seen that the current spread of the 10 year Gilt yield vs inflation is lower than the periods before the 2008 financial crisis (admittedly a snapshot vs an average, but a snapshot taken when inflation is at a recent low- and since when 10 year Gilt yields have dropped again to 4.1%)

In the end, the bond market provides certainty of nominal returns, but none over real returns. If you are happy locking in +/- 4.25% before tax over a 10 to 30 year term in sterling, the opportunity is there in the Gilts market. If you are not, then higher short rates are available- whether six month T-bills (still yielding over 5%), in short gilts (which benefit from the Capital Gains tax exemption if purchased at a discount), by corporate bonds (also in some cases shielded by the QCB exemption) or by medium term notes issued by UK SMEs under secured programmes arranged by LGB. Here at LGB we continue to be strong advocates of the fixed income laddered portfolio, encouraging investors to invest in different issues with extending maturities and to buy-and-hold, in order to benefit from regular cash flows through interest payments and redemptions, increasing resilience against market volatility. More detail on how to establish a laddered portfolios of fixed income and the different fixed income opportunities you can access via LGB can be found on the LGB Deal Hub.

One reason to keep a meaningful weighting in bonds, and to balance the duration risks with a laddered portfolio, is the plethora of emerging political risks. I have not commented on China, but here are some thoughts on developments and events closer to home. These have come thick and fast over the last few years- the invasion of Ukraine, the Truss / Kwarteng budget, even the Euro elections and Macron’s decision to call a snap election in France. Leaving aside as we must the unknown unknowns, it is worth spending some time on the following:

POLITICS

- The new Labour administration in the UK. Probably the least surprising! And maybe even some opportunities?

- France- which arguably is just showing signs of the increased polarisation of politics we’ve seen elsewhere in Europe (maybe even in the UK)

- And consequently the tension between the European Commission and an EU with an increasing number of member countries who are no longer aligned with its objectives and values- no longer just Orban in Hungary.

- The return of Donald Trump to the White House after the next US election (the betting odds are currently Trump 8/13 on to win…Biden 13/2 against, Kamala Harris the same).

Let’s take these in turn and think about potential consequences.

The UK

In the UK, we have in the Labour manifesto a mix of aspirations which will cost money and commitments to keep at least certain taxes more or less unchanged. The desire for growth is uncontroversial, and the willingness to ease planning controls a necessary step forwards, but one which will take time to put in place. There are certainly some opportunities:

- House builders should be able to capitalise on this, if they can find the skilled workforce. And if Labour can reverse some of its policies in opposition as for example over nutrient net neutrality. It’s interesting that there is corporate activity emerging in the sector – Crest Nicholson has attracted interest including a £650m bid from Bellway, and the auction of Legal & General’s Cala will be an interesting test case- Persimmon is reportedly considering a £1bn bid.

- The commitment to modernise the NHS is something that probably only a Labour administration can carry out. The new health Secretary, Wes Streeting- having scraped home as an MP- has been open in his willingness to collaborate with private sector service providers offering solutions, of which there are many, often run by ex NHS employees (for example Feedback plc which is listed on AIM). The NHS’s productivity problem is in large part due to its failure to invest in systems and equipment. However a resolution of the junior doctors’ strikes will divert funding, and the embedded conservatism of the medical profession and limited competence of the NHS bureaucracy may mean change is hard to deliver.

- “Great British Energy” does not feel like a game-changer- maybe there will be some money available for green energy companies, but it would be unwise to count on it. Competitors to AFC, ITM and other fuel cell, electrolyser and battery companies in the USA have received largescale government support – might it happen here? Possibly National Grid’s pre-emptive strike by raising enough equity to fund major spending on grid upgrades will make it an interesting investment, particularly if rates do go down.

So- what are the risks? The legacy of the Truss/Kwarteng experiment has presumably prevented the risk of unfunded spending- but taxes will surely rise. VAT on education will not bring in as much as hoped (a mix of children leaving the sector, delays from judicial reviews, and brought-forward tax credits from building work done over the last ten years). Anecdotal evidence about non-doms relocating seems well founded. So- look out for changes to the upper bands of Council Tax, reviews of inheritance tax breaks (top limits on the value of farms?), and as the inability to spend on desired projects becomes more painful, calls from within the party for new taxes. Wealth taxes? Clawbacks on pension pots? Plus a very large number of seats implies a very large number of backbenchers who are not on the government’s payroll and who may not wish to toe the line.

In so far as there is a strong Blairite influence on Keir Starmer, a couple of years of proving fiscal responsibility (as after the 1997 election) before starting to spend more heavily may be the way things play out, and an election in two years, looking for a mandate for a more radical set of policies and a more aggressive approach to tax might appeal. That might be more scary for owners of assets.

Europe

The two interlinked stories are the rise of the right in the EU elections, and Emmanuel Macron’s voluntary loss of control of the National Assembly. There are therefore two general risks coming from the Continent: the specific French risk to interest rates, with divergence coming from a major economy, and the more general medium term risk that the rise of Putin-friendly (or at least anti-interventionist) regimes and parties across Europe helps contribute to a clear Russian victory in Ukraine, and a consequent threat to other states, particularly in the Baltic.

Arguably the underlying problem across Europe including the UK is that low growth and higher interest rates, plus the region’s ever-decreasing share of the world’s economic power, means that voters’ expectations of better services and ever rising living standards as well as no tax increases simply cannot be delivered. On top of this demographic pressures are forcing governments to import labour without being explicit about what they are doing, providing fuel for the fire of anti-migrant parties. At the same time the Ukraine invasion has forced governments to think about increasing defence spending.

The result of the second French election, leaving the new and hastily assembled Nouveau Front Populaire as the largest grouping, and within that Melenchon’s very left-wing France Insoumise as the largest party, will make for a confusing period, a substantially weakened president, and presumably another election when Macron is allowed to call one, in a year. The NFP wants to roll back pension reforms (returning the retirement age from 64 to 60), restore wealth taxes and generally advocates a tax and spend approach. The FT’s analysis commented that it included “moderate” left groups such as the French Communist party which is an interesting reflection on its colouring. Analysis by the Institut Montaigne costed the pension change at €58bn a year, and price caps at €24bn. Other economics measures included scrapping free-trade treaties (in practice presumably this means vetoing new EU ones and stopping extensions).

France has for years run a budget deficit above the limits of 3% of GDP in theory allowed by the EU – it was 5.5% last year. A worsening of this position can only create tension with Brussels, with Berlin, and with other northern EU countries. And French politics will remain confused. The right wing RN was defeated but is now the largest single party and has the largest number of seats it has ever gained, plus can stand back from the inevitable squabbling that sustaining a coalition will entail.

The USA

Donald Trump seems to have managed to convince a large number of Americans that things were better when he was president, that the incumbent is senile and that he is not a crook. As noted, the bookies’ odds favour his return to the White House. Whilst the Democrats are not exactly sound on free trade and a rules-based world economic order, Trump is deeply suspicious of both, and threatens to use large-scale tariffs to favour US domestic industry. He continues also to take the view that NATO states have had a free ride on US defence spending, and has come close to a major reduction of US involvement in the defence of Europe. From a European point of view his combination of tariffs, his lack of interest in pushing back on Russia in Ukraine and his increasing pressure on China (given particularly German industry’s big bet on it) represents a cluster of threats. His lack of interest in budgetary restraint (a reflection, a cynic might argue, of his approach to financing his companies over the years) and the perception that his programme would be inflationary through tariffs and migration restrictions only increase the danger of an outbreak of bond vigilantism in the Treasury market and a consequent rise in rates for the US and therefore unavoidably, for most of the rest of the world. There is already no shortage of commentators arguing that the US deficit is unsustainable. Like the cartoon character Wile E. Coyote, you can run off the cliff and keep going – unless you start looking down.

Conclusions

Big political changes can have big market effects- witness the outperformance of defence stocks since the Ukraine invasion- both for good and for ill. In the bond markets most of the dangers seem to ones that keep rates higher for longer (though we know now that central banks will tend to take rates down sharply if there are really serious problems)- so Labour borrowing more to finance investment, the new French assembly sabotaging Macron’s attempts to restore at least a little fiscal responsibility, Trump letting borrowing rip, all tend to push in that direction. In which case bond portfolios relatively short duration and taking advantage of current interest rates makes sense. For equities there isn’t a corresponding response, but investors do need to keep an eye on where government investment plans or other policy changes create opportunities- and also to bear in mind that political shocks and a “risk off” response from markets can lead to sharp downward moves.